Abstract:

When MLB (Major League Baseball) agreed on a new Collective Bargaining Agreement in 2012, the Qualifying Offer system was instituted within MLB free agency. The new system effectively changed how players entering free agency were being evaluated in the market. In order to measure the AAV (Average Annual Value) of the Qualifying Offer, three years of signing/extension data from 2012 to 2014 was used for an ordinary least squares (OLS) regression analysis. Through this analysis, the goal of this document is to explore the decision-making process for MLB teams during the offseason free agency period. Thus, the OLS regression analysis provides an understanding of the valuation process for MLB free agents and shows high accuracy for future transaction predictions.

Keywords: Nonparametric, Realized Volatility

JEL Codes: L83

⇤ Special thanks to Dr. Philip Shaw for his guidance and contribution

1. Introduction:

The Qualifying Offer in MLB free agency has been a hot topic in its first three years in existence since 2012. The new system has created market efficiency, where MLB teams must weigh the pros and cons of losing or signing a free agent. For any team looking to offer or sign a Qualified Offered player to a contract must weigh three decisions during the process. Those three decisions include; the player's value to the team, the team's draft pick status, and the desirability of the player within the free agent market. All of those factors play a huge role in the economics of modern-day MLB free agency. With MLB being one of the only sporting leagues in support of relatively open salary caps, team budgets differ widely among the 30 MLB teams. Although seemingly counter intuitive, MLB teams with the highest average salaries are not necessarily the best teams. The best teams are constructed through sound economic decisions. This thought process is totally subjective on a team by team basis, but is still built on the foundation of value delivered based on the player's performance, contract or a combination of both. Rightfully so, the Qualifying Offer plays an important role in this decision-making process for MLB executives, who may be losing or signing their free agents.

2. History of the Qualifying Offer:

The Qualifying Offer in the 2012-2016 MLB Collective Bargaining Agreement represents a significant change from the previous 2007-2011 CBA's Type A/Type B compensation system. In the new system of free agency, “the qualifying former club of a Qualified Free Agent may tender the Qualified Free Agent to a one-year Uniform Player's Contract for the next succeeding season”, equivalent to the average annual salary of the top 125 salaries in baseball (2015, $15.3 million) (2012-2016 MLB, Article XX, Section B). “If the Player accepts the Qualifying Offer, he shall be a signed player for the next season on a one-year contract with a salary equal to the amount of the Qualifying Offer” (2012-2016 MLB, Article XX, Section B). However, if the Qualified Free Agent declines the Qualifying Offer and signs with another Major League Club, “the former Club of a Qualified Free Agent, subject to compensation, shall receive an amateur draft choice (‘Special Draft Choice’) in the next MLB Draft” (2012-2016 MLB, Article XX, Section B). To clarify, the ‘Special Draft Choice’ is a designated draft pick at the end of the first round of the MLB Draft. In the case of the signing team, “the Club that signs one Qualified Free Agent, who is subject to compensation, shall forfeit its highest available selection in the next MLB Draft” (2012-2016 MLB, Article XX, Section B). In congruency, the club does not have to “forfeit a selection in the top ten of the first round of the MLB Draft,” but is subject to forfeit their next highest selection (2012-2016 MLB, Article XX, Section B). In addition, if a club “signs more than one Qualified Free Agent, subject to compensation, shall forfeit its highest remaining selection in the next MLB Draft for each additional Qualified Free Agent it signs” (2012-2016 MLB, Article XX, Section B). This new system differs from the old Type A/Type B compensation system in two significant ways. First, in the past, “the former Club of a free agent could offer to proceed with the Player to salary arbitration for the next following season” (2007-2011 MLB, Article XX, Section B). If the Player agreed to the offer, “he shall be a signed player for the next season and the parties will conduct a salary arbitration proceeding”, which has known to be a subjective process (2007-2011 MLB, Article XX, Section B). Second, if the free agent declined the arbitration offer, “the former Club of a Player would become a free agent” and would be subject to compensation to the former team as a ‘Type A or B Player’ in the ‘Statistical System for the Ranking of Players,’ which used two-year average of statistics for each respective position group (2007-2011 MLB, Article XX, Section B). Type A free agents were designated based on, “who ranks in the upper twenty percent (20%) of his respective position group” (2007-2011 MLB, Article XX, Section B). If a Type A free agent signed with a new team, the former Club of the free agent would acquire the new signing team's first round draft pick and a ‘special’ draft pick in the compensation round (2007-2011 MLB, Article XX, Section B). For example, if the Type A free agent signed with Team B, Team A would receive Team B's first round pick and compensation pick at the end of the first round. While, Type B free agents were designated based, “who ranks in the upper forty percent (40%) but not in the upper twenty percent (20%) of his respective position group” (2007-2011 MLB, Article XX, Section B). In this case, if a Type B free agent signed with a new team, the former Club would only receive a ‘special’ draft pick (compensation round pick) (2007-2011 MLB, Article XX, Section B). The major problem with the old Type A/Type B compensation system was too many players were being designated as Type A or Type B free agents. Essentially, it caused inflation on player value because the free agent designation was only relative per position. In the last year of the old system, the ‘Statistical System for the Ranking of Players’ designated 37 players of being either Type A or Type B free agents. With the new Qualifying Offer system, the free agency market has become more efficient, where teams are forced to assess the value of their own players. Instead of 37 players being translated into 37 potential ‘special’ draft picks, the Qualifying Offer system creates a slimmer market, where a player's past/future performance value are more equivalent to proper dollar value.

3. Data and Methodology

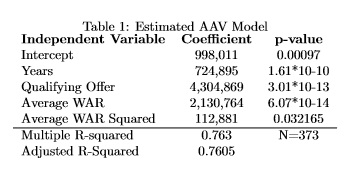

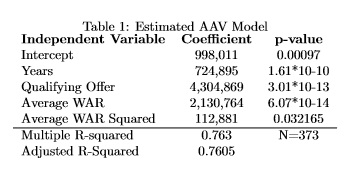

yi = β0 + β1x1 + β2x2 + β3x3 + β4x4 + u

In order to best explain the effect of the Qualifying Offer, signing/extension data from 2012 to 2014 was used to build the explained model. Only three years of signing/extension data was used because the Qualifying Offer system only began in 2012. Thus, within the analysis performed, a sample size of 373 was used. To measure the dollar effect of the Qualifying Offer, ordinary least squares (OLS) regression analysis was used. AAV (Average Annual Value) was used as the dependent variable within the model. To define AAV, it is the price that a team pays for its player on an annual basis. Although it would seem logical to use the total dollar amount as the dependent variable, AAV is an easier variable to use in order to measure the annual effect of the three independent variables. After running a regression with AAV, as shown in Table 1, 76.3% of the variation in AAV is explained by the independent variables of Years, Qualifying Offer, WAR, and WAR Squared. Thus, the model acts as a fairly reliable predictor of properly valued AAV. As the first variable within the model, Years (assigned to a signed contract) was used as an independent variable because it proved to be significant towards player valuations. At first, Age was considered as an independent variable within the model. However, the Age variable was considered insignificant towards AAV. The most likely reason is that, by holding all other variables constant, AAV fluctuates too much with age. The Years variable proved to be a better independent variable and has a logical reasoning for a positive effect on AAV. With an incremental change in Years, AAV should increase consistently based on a higher value placed upon the free agent. By using Years as an independent variable, holding all other factors constant, the incremental change of Years increased AAV by $724,895. The Qualifying Offer was used as the second variable within the model. In order to label a player as a Qualified Offered player, a binary code was used for the variable. A Qualified Offered player was designated with a 1. While, a non-Qualified Offered player was designated with a 0. Based on the model, with the use of ceteris paribus, the effect of the Qualifying Offer on AAV is shown to be $4,304,869. Average WAR and Average WAR Squared were the third and fourth variables used within the model. An average of three years of player WAR data was used in order to really understand the true indicative performance value of a player. There were two factors that were important in the use of WAR. First, a measurement for player performance was needed to properly valuate player performance towards AAV. Second, the measurement needed to prove to be consistent between batters and pitchers. Average WAR proved to be the best measure for this regression analysis because it is a measurement that fulfills both factors. By holding other variables constant, the effect of WAR on AAV proved to be $2,130,764. An important variable was discovered through this analysis. The variable is an exponential term. As shown within the model, WAR has a marginal increasing effect upon AAV. The squared effect of WAR on AAV is shown to be $112,881.

4. Results

4.1 The Effects of the Qualifying Offer on AAV

Since the introduction of the Qualifying Offer in 2012, Qualified Free Agents, on average, earn ~$ 4.3 million more than Non-Qualified Free Agents. The reason for the difference in value, assuming all other variables constant, is most likely a result of desirability. 32 players have been offered the Qualifying Offer. However, in all 32 situations, the player has rejected the Qualifying Offer. The implications of understanding the dollar effect of the Qualifying Offer is important in both cases for the former club and the potential signing club. The free agency and trade market play an important role in offering or signing a Qualified Free Agent. If a player of the same performance value is available on the market, it might actually prove to be beneficial to avoid offering or signing the Qualified Offered player. Another important factor in play with the Qualifying Offer are the draft slot bonus allotments. As mentioned before, any former team, who loses their Qualified Free Agent to another team, will gain a compensation pick at the end of the first round of the MLB Draft. For instance, in the 2013-2014 offseason, the Cincinnati Reds offered the Qualifying Offer to Shin-Soo Choo with the knowledge he would reject the offer in pursuit of a long-term deal. With long-term deals already tied to Joey Votto, Homer Bailey, Jay Bruce, and, potentially, Johnny Cueto, resigning Shin-Soo Choo was not an option for the Reds and the acquisition of compensation pick was actually worthwhile for the club. In the case of any signing club, who signs a Qualified Free Agent, must relinquish their first round pick (Pick 1-10 protected, in that situation, next highest pick). For example, when the Texas Rangers signed Shin-Soo Choo to a 7 Years, $130 million deal, the Rangers effectively forfeited the 20th pick in the 2014 MLB Draft (Crasnick). The 20th pick would have ensured a slot bonus allotment of ~$2 million. Thus, the Rangers essentially were willing to pay the premium on the differential between the value of the Qualifying Offer and the 20th pick slot bonus for the services of Shin-Soo Choo. Obviously, there is risk involved with forfeiting a draft pick and signing the Qualifying Offered free agent. The biggest risk is achieving the expected value from the player over the course of the contract. In any situation, the team is paying based on past performance. Thus, it is no guarantee that the future performance will reflect on past success. Hence, it is important for any team to weigh the decision to sign a Qualified Offered Free Agent based on factors such as the strength of their farm system, the performance value of the player, and the quality of the team. As a final point, the presence of the Qualifying Offer seems advantageous for players because it creates a market, where high performing MLB players are paid for their worth as evidence from the ˜$4 million differential in Qualifying Offered Free Agents and Non-Qualified Offered Free Agents. The Qualifying Offer is an interesting change from the Type A/Type B compensation system of the 2007-2011 MLB Collective Bargaining Agreement. Instead of incoming free agents being designated as compensation or non-compensation assigned players, the Qualifying Offer forces MLB teams to place a value on their players. In many arguments within baseball circles, people have thought of the loophole to the Qualifying Offer system as teams submitting Qualifying Offers to all of their soon to be free agents. However, the Qualifying Offer system disincentivizes this type of action. For example, if the model above predicts the player’s value as ˜$10 million per year based on 3 years of WAR, a given Qualifying Offer incentivizes the player to take the offer. Thus, the team will automatically be paying ~$4 million more than the player is actually valued at without any type of negotiation process. Obviously, the specificity of the position, performance value, and age play very important roles in this type of analysis of the free agency market. The best example of the Qualifying Offer exhibiting better efficiency in the market was Stephen Drew’s signing situation during the 2013-2014 offseason (Edes). Being valued at ˜$9.5 million after a productive 3.4 WAR season, the Red Sox offered Drew the Qualifying Offer, which at the time was approximately $14.1 million. At the time, Drew quickly rejected the Qualifying Offer. As time passed during free agency, it was quickly evident that his value was diminished in the eyes of other MLB teams, who saw Drew as not being deserving of the Qualifying Offer. In other words, MLB executives viewed other players of having equal or more value (in terms of WAR). Another factor that played a huge role in the diminished value of Drew was the attachment of a first round pick (highest draft pick). In retrospect, Stephen Drew should have signed the Qualifying Offer because, at the time, the Red Sox were valuing Drew at a number far beyond his worth. Although the Red Sox were able to sign Drew at a cheaper deal than the Qualifying Offer, the strategy of sending Qualifying Offers in a less strategic method points to inefficiency of the teams valuation of their own players.

4.2 The Effects of WAR on AAV

Another piece of information that plays a huge role in establishing a player's AAV (average annual value) is WAR (Wins Above Replacement). WAR is a summarization of a single player's total contributions in one statistic against the league and position average (Fangraphs). WAR is split into two sections; position players and pitchers. In the case of position players, a player's batting, running, and defensive performance are measured against the major league average, adjusted per position, and adjusted for park factor (Fangraphs). For pitchers, WAR is calculated through FIP (Fielding Independent Pitching) and measured against the league average for pitchers and is adjusted for park factor (Fangraphs). On the internet, there are many sets of WAR data available because there is no one exact interpretation for the measure. However, the different WAR databases available usually reach the same conclusion on MLB players. In this analysis, Fangraphs' WAR was used because their data sets take into account advanced peripheral data for evaluating position player/pitcher performance. Based on the data analysis, WAR's relation to AAV increases exponentially, meaning that the rate of change of WAR is found by y=WAR+(2*WAR), holding all other variables constant. In the case of 3 years of free agency and extension data, MLB teams are currently willing to annually pay $2,356,526 for every additional point of WAR.

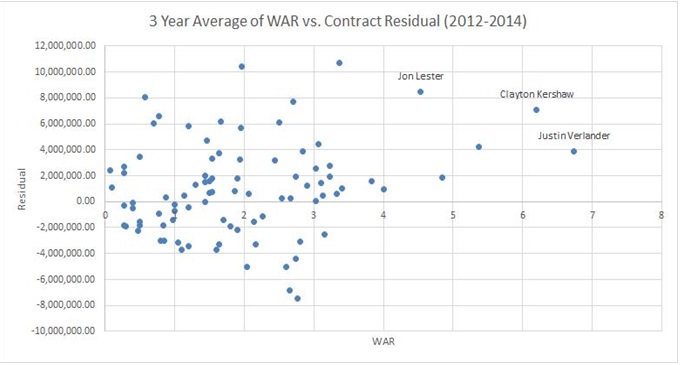

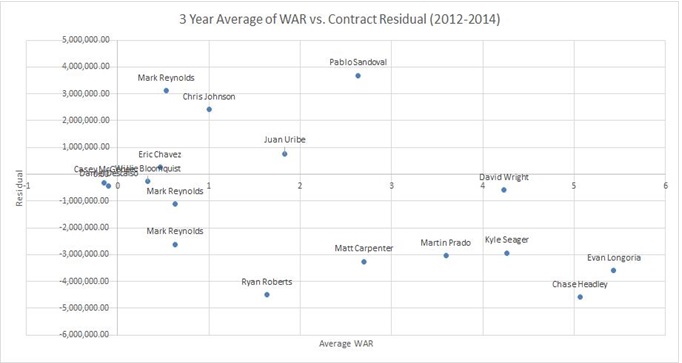

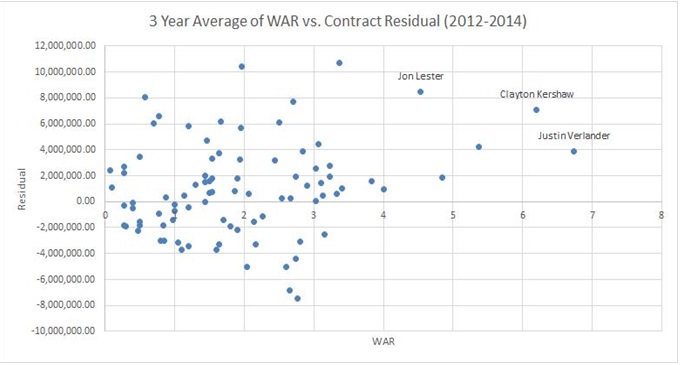

4.3 2015 MLB Free Agency Case Study: Jon Lester

Jon Lester was drafted in the second round of the 2002 MLB draft by the Boston Red Sox. He made his debut with the team in 2006 and was considered as a cornerstone ace in his 8.5 year tenure with the team. With the Boston Red Sox in last place in the division nearing the trade deadline, the Red Sox made the decision to trade Lester to the Oakland Athletics for left fielder, Yoenis Cepedes (Browne). With Lester approaching free agency in the upcoming offseason, the trade had major implications on his free agent status. By being traded midseason, the Oakland Athletics did not have the ability to extend a Qualifying Offer to the star pitcher. Thus, effectively eliminating the Athletics from having a chance at signing Lester. With the Oakland Athletics losing in Wild Card game against the World Series Finalist in the Kansas City Royals, the sweepstakes for Jon Lester effectively began. After receiving competitive offers from the Boston Red Sox and San Francisco Giants, Jon Lester chose to sign with the Chicago Cubs for 6 years, $155 million (ESPN). Based on the model provided above, the Cubs paid $8,506,658 more than the predicted value annually (Figure 2). This ultimately means that over the course of the 6 years of the deal, the Cubs overpaid nearly $51 million for Lester’s services. Although Lester was able to perform at a 6 WAR in 2014, he has never performed at a high enough level to justify a nearly $25 million per year contract. In defense of the Chicago Cubs, one huge factor was in play for their decision to overpay for Jon Lester. With no draft pick attached to Jon Lester in the form of a Qualifying Offer, teams such as the San Francisco Giants and the Boston Red Sox were more willing to get into a price war for Lester's services. In the case of the Chicago Cubs, Theo Epstein began his tenure as the President of Baseball Operations for the Cubs in 2011 and began to rebuild the foundation of the team's minor league/major league system. The Jon Lester signing signals the change from rebuilding to contending. Over the three year tenure of Theo Epstein, the Cubs have cultivated many promising players such as Javier Baez, Kris Bryant, and Jorge Soler (Keown). Thus, Epstein accepted the fact that he overpaid for Lester's services, but it is clearly predicated on maintaining a 3-5 WAR per season (indicative of top of the rotation starter) (Figure 3).

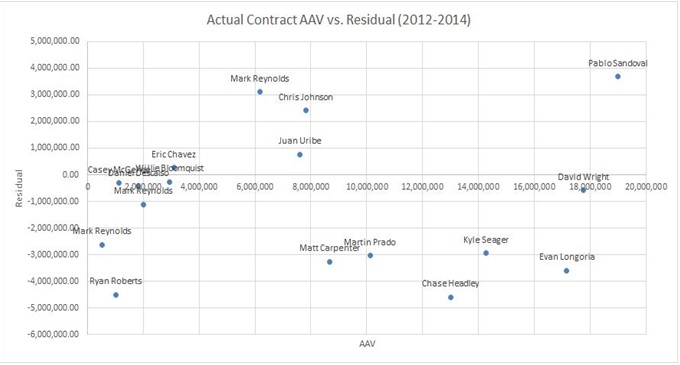

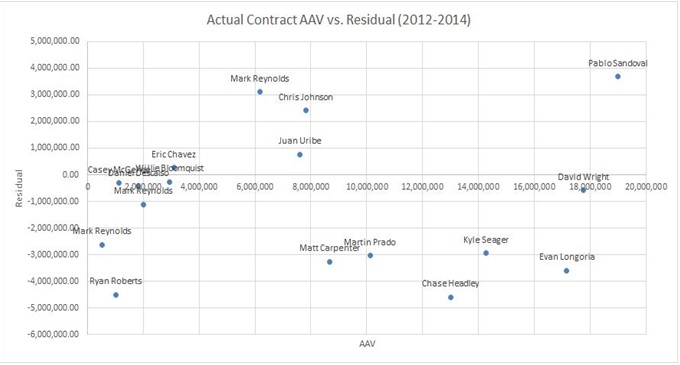

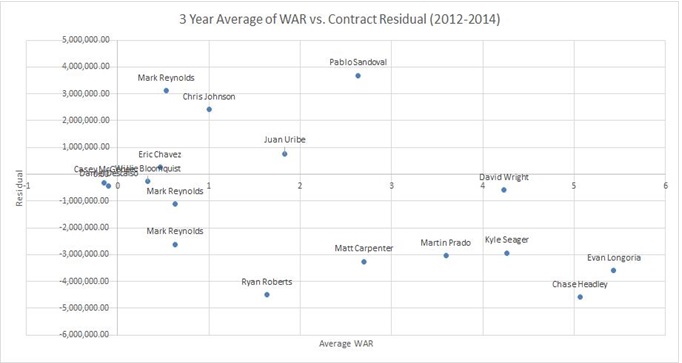

4.4 2015 MLB Free Agency Case Study: Pablo Sandoval

Pablo Sandoval has followed a career path that is far unique from Jon Lester. As a 16 year old, he signed a minor league deal with the San Francisco Giants as a catcher from Venezuela. During his minor league career, he switched between third base, catcher, and first base. However, after playing only a handful of games at catcher at the major league level in 2008, Pablo Sandoval has played predominantly at the third base position. Since his debut season in 2008, Pablo Sandoval has become known for three things; phenomenal contact percentages, weight, and clutch postseason play. In a five year span since 2010, Sandoval has the highest outside contact rate per outside swing rate of any player in MLB by a wide margin. In other words, he is able to consistently open up his swing-zone and put the bat on the ball at a phenomenal rate compared to his peers. In terms of clutch postseason play, he has played a significant role in the San Francisco Giants' three championships in the past five years. After the Giants won the 2012 World Series, Pablo Sandoval was named MVP of the series. Specifically, he is most remembered for his three home run performance in Game 1 of the World Series, which is a record only replicated by three MLB all-time greats; Babe Ruth, Reggie Jackson, and Albert Pujols (ESPN). In this past World Series victory, he replicated his prowess for clutch hits, by generating a momentum turning double in the late stages of Game 7, which ended up being the game-winning run. If any criticism could be parlayed onto Sandoval, it is his weight. Although Pablo Sandoval was able to keep his weight below 240 pounds during this past season, many executives in the past have been concerned about his durability over a long 162 game season because of his inability to keep his weight in check. After six years of arbitration control, Pablo Sandoval hit the free agency market this offseason. As duly noted, by the model, Sandoval was projected to have an AAV of ˜$15.3 million per year. With Sandoval playing a full year in San Francisco in 2014, the Giants offered him the Qualifying Offer, valued at $15.3 million, and he quickly rejected the offer in search of a long-term deal. After fielding long-term offers from the San Francisco Giants, Toronto Blue Jays, San Diego Padres, and Boston Red Sox, he ultimately chose to sign with the Boston Red Sox for 5 years, $95 million (ESPN). Based on the model, it seems that the Red Sox signed Sandoval ˜$3.6 million annually more than the projected annual value (Figure 4). Overall, the Red Sox overpaid Sandoval by ˜$18 million. Although the Red Sox forfeit their highest pick (second round pick), the price of an extra $18 million is reasonable. One important perspective to take into account for this signing, the Red Sox in the 2015 draft have protected top ten pick. This presents a win-win situation for a top ten pick protected team like the Red Sox, who are able to weigh the difference between a second round pick (value of less than $500,000) against the Qualifying Offer (Value of $4.3 million). In this case, it is a no-brainer for the Red Sox to pursue Sandoval's services. When you take a look at the moves the Red Sox have made this offseason in the form of trades and signings, they are dedicated to putting a winning team on the field this 2015 season. After winning a World Series in 2013 and not even making the postseason in 2014, the Red Sox have put themselves in a win-now situation with David Ortiz and Dustin Pedroia being the core to hold it all together. Pablo Sandoval fits this perspective perfectly because he is still in the prime of his career at the Age of 28 and has shown to be an above-average player at the third base position. The contract is predicated on Sandoval maintaining a 2.6 WAR over the course of the five year deal, which is fairly reasonable for a player of his nature (Figure 5). Obviously, the maintenance of a high-level of fitness and functional weight will be a concern for Pablo Sandoval going into the future. However, with a strong clubhouse in Boston, the same motivation for Sandoval to stay fit, already exhibited in San Francisco, should not be a concern as he continues to play into the prime of his career.

5. Conclusion

As read through this analysis, the new free agency system is simpler than the old Type A/Type B compensation system. Still, the intricacies of the Qualifying Offer system are rather difficult in action. As seen through this analysis, with performance constant (in terms of WAR), Qualifying-Offered players make approximately $4.3 million more than non-Qualifying Offered players. In this case, teams must carefully weigh the value of impending free agents to the value of their team and the free agency market. If an impending free agent's past/future performance value does not justify the use of the Qualifying Offer, the team should not offer a Qualifying Offer or sign a qualifying offer attached player. In this case, the reason is there are players of equal or better performance value available at a far lower price in the free agency market. As described in the Stephen Drew’s Qualifying Offer situation in the 2013-2014 offseason, the impending free agent actually has an incentive to sign the offer based on the team's inflated perception of the free agent's value in comparison to the market. Still, as a decision-maker in the free agency market, it is more important to not look at a high AAV residual and immediately declare a team overpaid on a free agent. The free agency market is run like any industry, where there is a fixed supply and a fluid demand. Thus, in the case of the model above, the most effective way to really gauge the quality of the contract is to look at the WAR (average WAR over 3 years) and, then, determine whether the player can maintain that WAR over the course of the contract based on factors such as age, potential, and make up in comparison to the contract value given. For example, Jon Lester's model predicts an AAV of ˜$17.3 million, but is being paid at a premium AAV of ˜$25.3 million. If he can perform at a 3-5 WAR over at least four years of a six year deal (Age 31-35), he could possibly be delivering between $49 and $54 million in performance. Even though Lester would be paid ˜$101.6 million for the first four years of the deal, many pitchers in MLB cannot replicate the same dollar amount in performance. Hence, value in MLB free agency is determined in a team's own valuation of its own players and the free agency market. With the cost of a win increasing on an annual basis, the effects of the Qualifying Offer and WAR on player salary (AAV) will continue to play an important role in player valuations until the next CBA agreement.

References:

”2007-2011 MLB Collective Bargaining Agreement.” MLB.com. MLB, n.d. Web. 11 Jan. 2015. http://www.steroidsinbaseball.net/cba/cba 07 11.pdf.

”2012-2016 MLB Collective Bargaining Agreement.” MLB.com. MLB, n.d. Web. 11 Jan. 2015. http://mlb.mlb.com/pa/pdf/cba english.pdf.

Browne, Ian. ”Lester Goes to A’s for Cespedes in Swap of Stars.” Major League Baseball. MLB, 31 July 2014. Web. 11 Jan. 2015. http://m.mlb.com/news/article/87221336/red-soxtrade-jonlestertoasforyoeniscespedes.

Crasnick, Jerry. ”Rangers Land OF Shin-Soo Choo.” ESPN. ESPN Internet Ventures, 21 Dec. 2013. Web. 11 Jan. 2015. http://espn.go.com/dallas/mlb/story/ /id/10176085/texas-rangers-signshinsoochoo7yeardeal.

Edes, Gordon. ”Red Sox, Stephen Drew agree.” ESPN. ESPN Internet Ventures, 21 May 2014. Web. 11 Jan. 2015. http://espn.go.com/boston/mlb/story/ /id/10959122/bostonredsoxre-signshortstopstephendrew.

ESPN.com News Services. ”Jon Lester Chooses Chicago Cubs.” ESPN. ESPN Internet Ven-tures, 10 Dec. 2014. Web. 11 Jan. 2015. http://espn.go.com/chicago/mlb/story/ /id/12008073/jon-lestersignchicagocubs.

ESPN.com News Services. ”Jon Lester, Giants Set To meet.” ESPN. ESPN Internet Ventures, 1 Dec. 2014. Web. 11 Jan. 2015. http://espn.go.com/mlb/story/ /id/11938036/free-agentleft-handerjonlestersan-franciscogiantsmeet.

ESPN.com News Services. ”Pablo Sandoval Hits Three Home runs.” ESPN. ESPN Internet

Ventures, 25 Oct. 2012. Web. 11 Jan. 2015. http://espn.go.com/mlb/playo↵s/2012/story/ /id/8548628/2012-worldseriespablo-sandovalhitsthreehomerunsopener.

ESPN.com News Services. ”Red Sox to Sign Pablo Sandoval.” ESPN. ESPN Internet Ventures, 25 Nov. 2014. Web. 11 Jan. 2015. http://espn.go.com/boston/mlb/story/ /id/11929658/boston-redsoxpablosandovalagreedeal.

Fangraphs. ”What Is WAR? — FanGraphs Sabermetrics Library.” What Is WAR? — Fan-

Graphs Sabermetrics Library. Fangraphs, n.d. Web. 11 Jan. 2015. http://www.fangraphs.com/library/misc/war/. Keown, Tim. ”Wait until Next, Next, Next year.” ESPN. ESPN Internet Ventures, 27 Mar.

2014. Web. 11 Jan. 2015. http://espn.go.com/mlb/story/ /id/10622213/theoepsteinplans-rebuildchicagocubsblueprintbostonespnmagazine.

Figure 2: Residual Analysis

Figure 3: Residual Analysis

Figure 4: Residual Analysis

Figure 5: Residual Analysis

NOTE: All statistics accurate as of 02/01/15

By Sanjay Pothula

AriBall.com