Decade and MLB consultant for over two decades) and Fred Claire (World Series-winning general

manager of the Los Angeles Dodgers and member of the club’s front office for 30 years.)

Media is welcome to use this information. We would ask for a reference and, if possible, a link to AriBall.com.

###

The Houston Astros weren't supposed to be good this year. Sure, there are a lot of exciting prospects either getting their first tastes of major-league action (George Springer and Jon Singleton) or getting within sniffing distance (Mark Appel and Carlos Correa). But going into the season, the staff ace was Scott Feldman. Scott Feldman is many things, but an ace is not one of them.

So it was much more than a pleasant surprise when, earlier this year, Dallas Keuchel suddenly became a front-end starter. After two major league seasons with ERAs in the 5s (supported by high FIPs), Keuchel has hit his stride and currently boasts a 2.63 ERA, good for 15th in MLB. His FIP and xFIP have similarly improved. He's thrown almost 100 innings this season, making it harder and harder to explain this away as a trick of small sample size. Dallas Keuchel is pitching like an ace. Why?

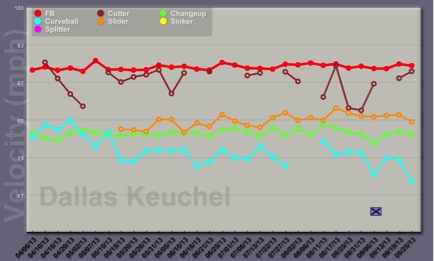

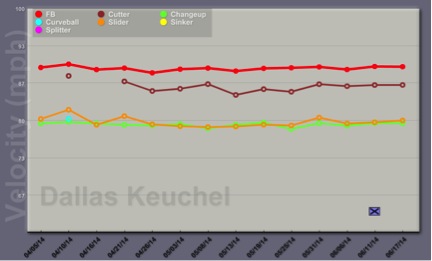

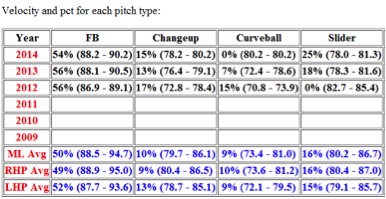

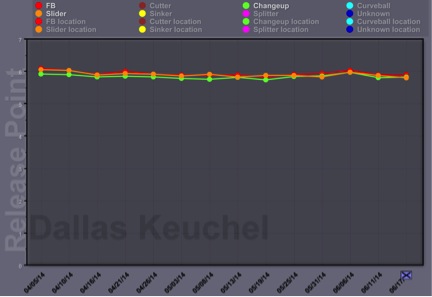

Oftentimes, a pitcher improves because he finds another tick on his fastball, which makes it less punishable and allows him more freedom in pitch selection. Yet, when we look at Keuchel's velocity charts, it's immediately obvious that he hasn't started throwing faster. His fastball is sitting resolutely in the 89 mph range, just as it did all of last year. That probably says good things about his lower risk of injury, and it means that if he did suddenly change his velocity, that injury-indicating change would be very noticeable--but it doesn't explain Keuchel's sudden breakout.

|

|

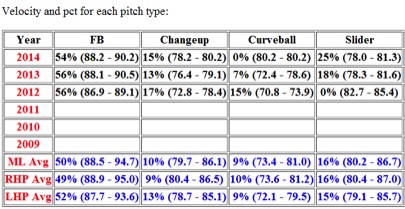

So taking another look at those charts, there's something very important. In 2013, Keuchel had a curveball. In 2014, he doesn't. Look at the data behind the graphs:

0 Curveballs in 2014. The data could not be more clear: Keuchel has completely ditched his curveball in favor of a slider. This has proved to be an exceedingly good choice. Looking at pitch values, his 2013 curveball was walloped and ended up at -5 runs above average. His slider, meanwhile, is a true swing and miss pitch, earning a 23.9% Swinging Strike rate (the 2013 curveball clocked in at 9%).

Keuchel's slider has a lot going for it. Starting purely at the level of the delivery, he gets some extra spin on his pitch.

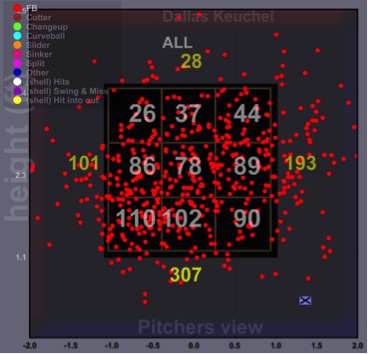

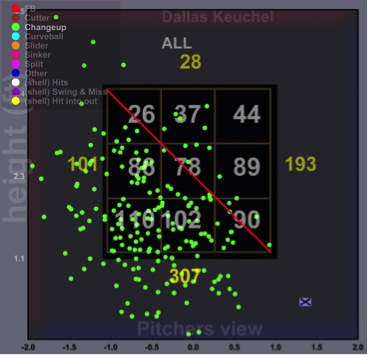

The slider rotates about 100 times more per minute than league average. Comparing it solely against the sliders of other left-handed pitchers, Keuchel gets 200 more RPM. This results in a pitch that has much more movement than average: 4.2 feet of horizontal break toward a right-handed hitter, as compared to the 1.3 feet that lefties average. It's no surprise that batters would have trouble hitting the ball. However, movement isn't everything--an unhittable pitch that can't be thrown for strikes is worthless, because batters will quickly learn to lay off it. But Keuchel also possesses great control. Here is where he has located his fastball and changeup.

|

|

Keuchel has almost entirely avoided the top of the zone. For a pitcher who struggles to hit 90 with his fastball, this is more or less a survival mechanism--he simply doesn't have the gas to consistently throw high. Instead, he spots the fastball low and away--note how thick the clustering is in the four bottom-left boxes. He's similarly aware of the dangers that threaten a changeup. The red line on the chart is a rough estimate of a typical right handed hitter's wheelhouse. On the season, only 15 changeups have been thrown there, most of them clustered close to the line.

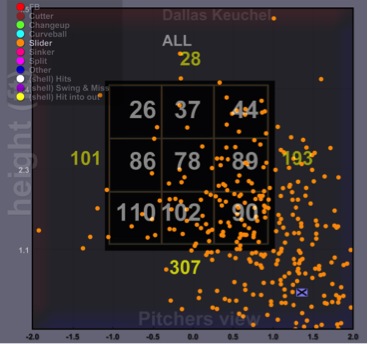

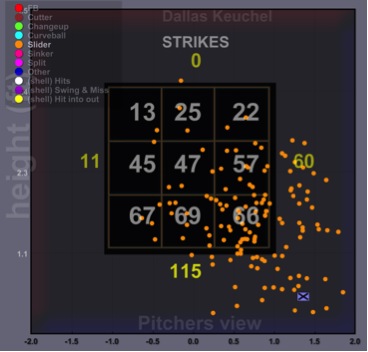

This zone positioning heavily emphasizes the outside. This is how the slider can be such a weapon. The charts below are all of the sliders that Keuchel has thrown, and then all of the sliders he's thrown for strikes.

|

|

I don't think my eyes are fooling me when I say he's gotten more strikes on sliders outside of the zone than in the zone. This is the swing-and-miss power of his slider. And if a batter doesn't whiff, it's very hard to punish a slider low and inside. It should come as no surprise that Keuchel's ground ball percentage is among the best in the majors (63.7%).

A quick digression: Keuchel was drafted 221st in the 2009 draft. He ranked as the 24th, 23rd, and 21st best prospect in the Houston system until he was called up. I say this to point out that his pedigree was not very impressive, with one exception. In 2010, he possessed the best chnageup in the California League. In 2011, it was the best in the Texas League.

Now, look again at the velocity charts, this time paying special attention to his changeup and his slider. The two are the same exact speed.

Needless to say, this is rare--a typical changeup is 5-7 mph slower than a slider. But because Keuchel's plus slider and plus changeup are the same speed, hitters have even more trouble differentiating them out of the hand. Their only option is to watch the release point out of the hand…

...or not. Keuchel throws his three pitches from the exact same spot, with precise control. Greg Maddux always claimed that hitters couldn't really recognize velocity, but even assuming they can, the slider and changeup would look exactly the same until they either broke straight down or darted laterally and down. The interaction of two already-good pitches makes both of them play up even further. The stuff Keuchel can do is the kind of thing that makes hitters shake their heads and sadly say "that isn't even fair."

NOTE: All statistics accurate as of 06/22/14

By Sam Whitefield

AriBall.com