The Mets have announced that Matt Harvey will start Game 1 of the World Series, followed by Jacob deGrom, Noah Syndergaard, and Steven Matz –

an order that most observers would have guessed, assuming Harvey’s triceps are healthy after being hit by an NLCS line drive.

This order allows the youngest members of the rotation

– Syndergaard and Matz – to enjoy some home cooking, but seems ideal to place a potential Game 7 in the hands of the man they call Thor, the 22-year-old rookie.

The truth is, choosing between Harvey, deGrom and Syndergaaard is not exactly the Goldilocks choice between the Three Bears.

These pitchers generally have the same profile.

Syndergaard throws the hardest, deGrom throws the “softest” and Harvey pitches to more contact than either, but the differences that create those realities are minute at best.

We’re talking about three aces

Before we break it down, let’s point out the obvious.

The Mets are moving from facing one type of offense to another – the Cubs struck out more than any team in the Majors (24.5 percent K%) and the Royals the least (15.9 percent).

Perhaps surprisingly, the Royals also walked fewer times than any Major League club, at a 6.3 percent rate.

(The offense happy Cubs and Blue Jays both posted a 9.1 percent rate only the 9.2 posted by the Dodgers; the Mets finished at 7.9 percent walk rate).

The Royals saw 3.71 pitches per plate appearance against the league average 3.82; the Mets were above average at 3.89.

So, for the Royals it’s all about putting the ball in play. Don’t think that they are a patient, work-the-count offense.

They are an aggressive team that seeks to use the whole field on offense.

Early-in-the-count pitches therefore will be more important than normal.

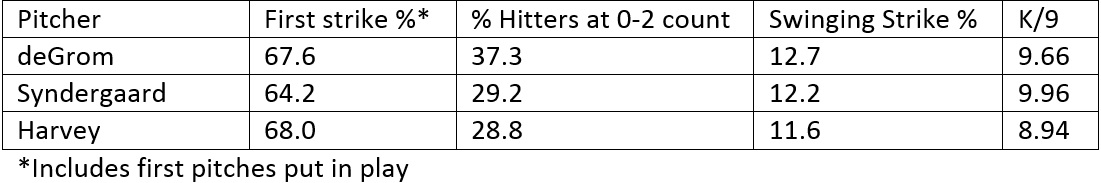

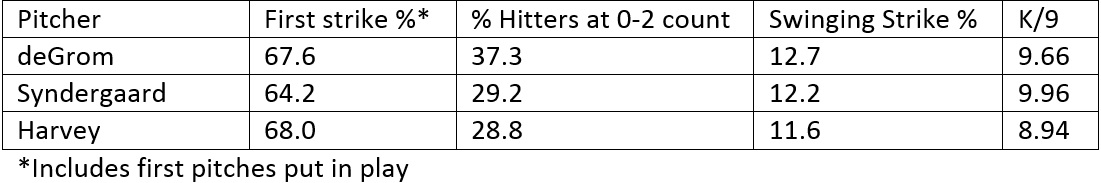

If strike one is the most important pitch, let’s see how the Mets’ big three fared early in the count and what percentage of total pitches resulted in a swing and a miss.

These numbers show each of the pitchers doing an excellent job of throwing strike one, with Harvey leading the pack.

deGrom though induces an 0-2 count more than 37 percent of the time, almost 30 percent more frequently than Harvey.

It’s interesting to note that Harvey earned strike one more often, yet owned the lowest K/9 ratio, indicating he may have been pitching to contact more often this season in an effort to limit his pitch totals.

The Swinging Strike percentage for deGrom, Syndergaard and Harvey are all excellent, particularly for starting pitchers.

By comparison, Yordano Ventura led the Royals starters with a 10.4 percent Swinging Strike percentage.

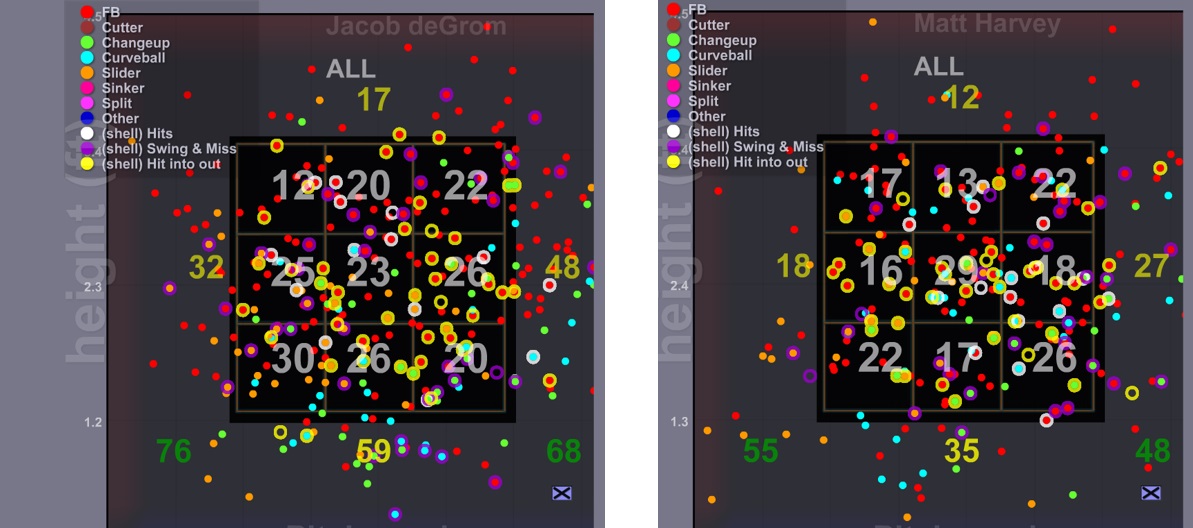

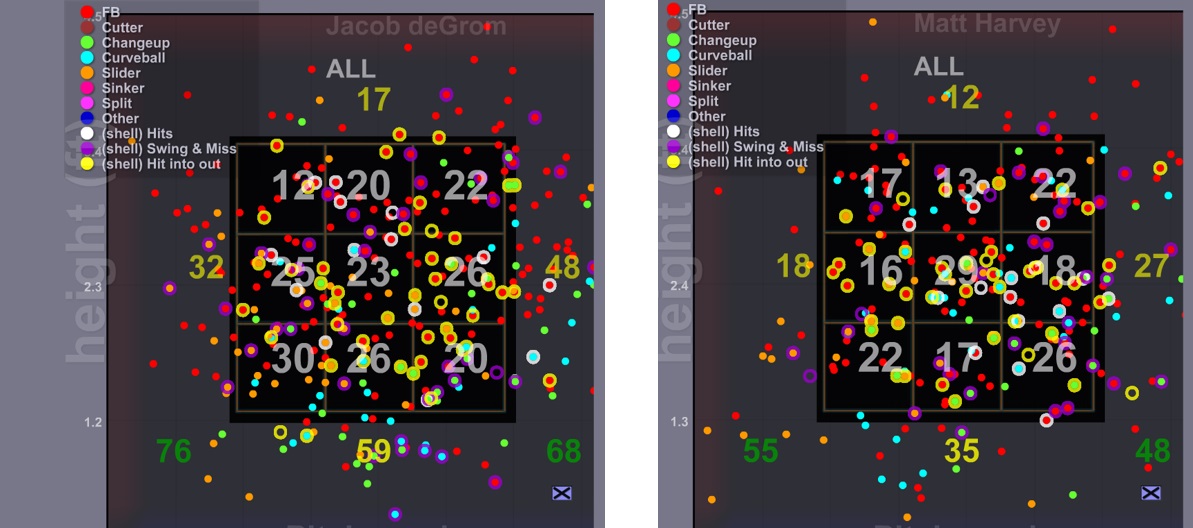

Here’s a look at all of the pitches on 1-1 counts thrown by deGrom and Harvey, to see if it shows us any difference in approach.

We’re looking to see if perhaps Harvey is pitching to contact a bit more. deGrom’s chart is on the left:

While those images may look more like modern art than an analysis tool, notice the cluster of pitches in the middle of the zone for Harvey.

deGrom spread the ball around the zone a bit more, particularly below the zone.

Looking at the numbers, we see Harvey surrendered a .268 BABIP on 1-1 counts; deGrom’s was just .200.

In all at-bats after a 1-1 count, both pitchers were very tough – Harvey yielded a .183 average and deGrom boasted a .164 average against.

Considering the first pitch batting averages against were .305 and .316 against deGrom and Harvey, respectively, and a little higher on 0-1 counts, expect the Royals to swing early and often.

The obvious downside is that if Kansas City is not effective early in the count, the Mets pitchers can go deep into the game.

But even getting to a 1-1 count looks to handcuff hitters.

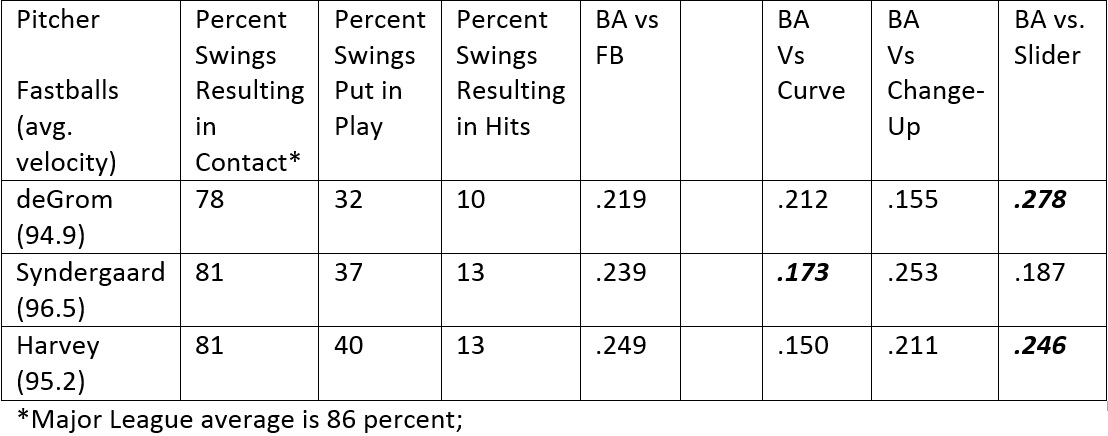

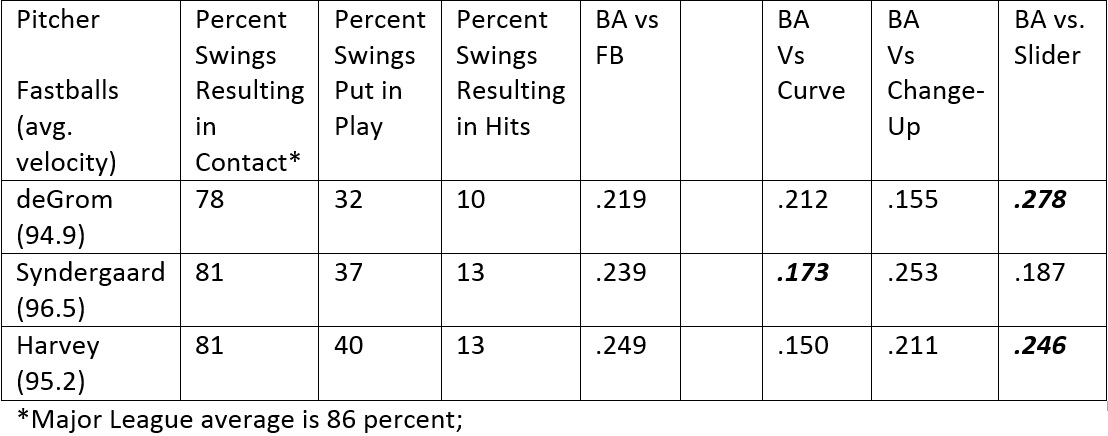

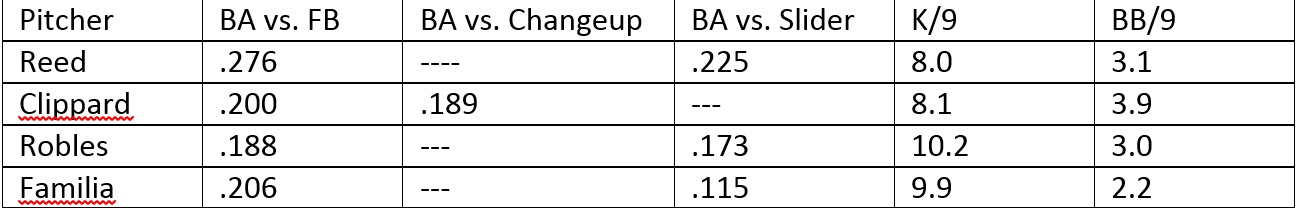

So the Royals, we know, want to make contact. The Mets starters, for the most part, want to miss bats. Let’s look at more AriBall data to determine what happens when hitters do make contact against the Mets’ Big Three. In the below chart, we look at the batting averages against each pitch type, looking a little closer at the pitchers’ fastballs, which make up more than 60 percent of each of their pitch totals.

Bold and italicized numbers indicate a pitchers second most frequent pitch, though the percentage differences between secondary pitches tend to be small.

As you can see, hitters made contact less often with deGrom’s fastball, which was actually the slowest on average of the three pitchers, though it should be noted that each were among the top 12 fastballs in terms of average velocity.

Those swings on deGrom’s fastball resulted in fewer balls in play and fewer hits. deGrom’s second best pitch is a devastating change-up which he throws almost as much as a less effective slider.

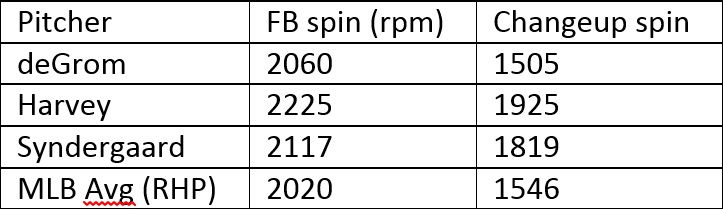

If deGrom’s fastball was not as fast as that of Harvey and Syndergaard, let’s dig a little deeper for find out why it was more successful.

deGrom did increase velocity on both his fastball and changeup by 1.5 mph, to 94.9 and 85.4 mph this season.

Harvey did not quite reach the same speed as in 2013 and of course Syndergaard is a rookie.

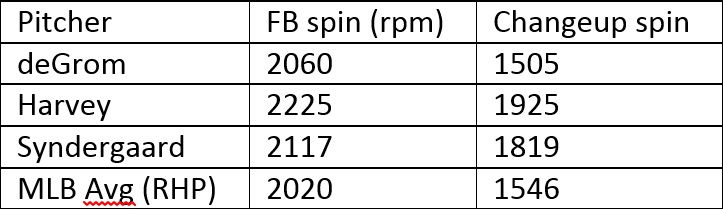

AriBall data shows us some interesting spin data on the fastballs and changeups for the trio:

Each pitcher has above average spin on his fastball.

Looking at the changeup spin, deGrom’s has a much slower spin than the other two, but is more inline with the league average for right handed pitchers.

That slower spin, remember, results in a lower break of the pitch but also slows the velocity and results in a more dramatic natural drop.

Perhaps deGrom’s precise release point combined with a fairly frugal use of the pitch increases the deception for a batter anticipating a fastball.

It will be interesting to observe during the World Series if Harvey and Syndergaard have a sharper “snap” to their changeup, and if deGrom’s seems heavier and therefore harder to make clean contact.

Each pitcher does a good job locating the pitch on the lower inside portion of the plate (to a right handed hitter), which helps in inducing ground balls.

The 22-year-old Syndergaard has relied on outright gas, a wicked curveball and a reliable slider to be effective in his rookie year.

Harvey’s curve was a nice out pitch, but he relied on a slider more than any other secondary pitch.

That pitch resulted a .246 batting average, slightly below that of his fastball.

To demonstrate the nature of the trio’s stuff, the batting averages against Bartolo Colon’s fastball, change-up and slider were .281, .275, and .287 respectively (he doesn’t feature a curveball).

So in Game 1, the key to Harvey’s success might be his ability to locate the curveball and fooling hitters with his changeup, the two pitches hitters have fared worst against.

If he can set those pitches up with early fastballs and sliders, he can dominate a very good lineup.

deGrom’s Game 2 success, as has been the case all year, will rely on his fastball and changeup, both of which he throws with great confidence.

Locating his curve is often the difference between an average and dominant performance.

So far in the postseason, deGrom has struggled with the command of his fastball early in games and he’s relied more heavily on his breaking pitches to fight through his outings.

The Royals might feast on a struggling fastball early in the count.

Syndergaard’s approach is simple – blow them away while also unleashing an impressive curveball.

His changeup pales in comparison to his rotation mates, but the rest of his stuff is just plain filthy.

The choice of Syndergaard in an often pivotal Game 3 and a potential Game 7 shows how much confidence manager Terry Collins has in the youngster.

One other note about the Mets pitching staff, specifically the bullpen:

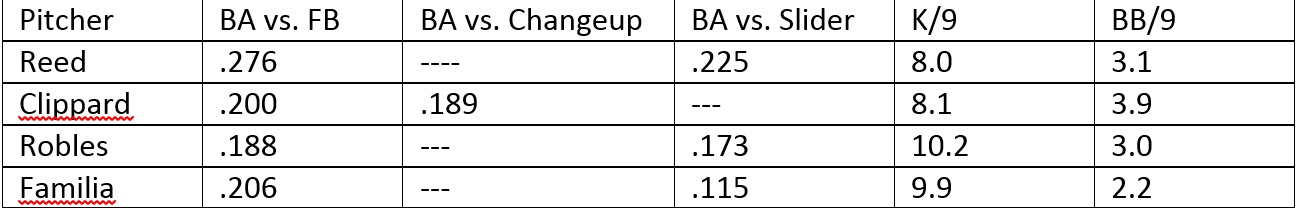

Terry Collins has been leery of using both Addison Reed and Tyler Clippard to set up Jeurys Familia, often using Colon and Jonathon Niese as bridges to their closer.

In a longer series, we would not be surprised to see rookie Hansel Robles play a larger role, perhaps in a set-up role.

Looking at the batting averages versus each pitch type, Robles looks like a better bet against an aggressive swinging team like Kansas City.

Robles fares just as well as Clippard, who has struggled late in the year. Robles has shown greater control and dominance, so we can at least see him taking over high-leverage opportunities or acting as a 6th/7th inning option for Collins.

He yields more fly balls than ground balls, which is surely a concern, but Reed’s fly ball tendencies are worse.

If, not when, the Royals make their way into the Mets bullpen, they will do themselves a favor by being a bit more patient than normal.

Robles and Familia have the stuff to strikeout any hitter, but Reed and Clippard are less dominant and therefore vulnerable to the big hit.

In any case, the Mets will face a much different team on offense in the Kansas City Royals and it will be interesting to see how the aggressive (mostly) veteran lineup fares against a staff that has been dominant this postseason.

References:

1. "Baseball Reference." Baseball-Reference.com. Baseball Reference, n.d. Web. 14 Apr. 2015.

2. "Baseball Statistics and Analysis | FanGraphs Baseball." Baseball Statistics and Analysis | FanGraphs Baseball. N.p., n.d. Web. 24 Apr. 2015.

NOTE: All statistics accurate as of 10/27/15

By Tom McFeeley

AriBall.com