The Los Angeles Dodgers made headlines on Wednesday when they traded away All Star second baseman Dee Gordon in a relatively shocking move that precipitated what would become a wild evening of maneuvering. By the end, the Dodgers ended up with former Angel Howie Kendrick taking Gordon’s place.

Kendrick marks a clear upgrade for the upcoming season, but Gordon is a young player who made a significant jump. The question for the Dodgers, though, had to be whether or not it was sustainable. After an excellent first half that got him his All Star nod, he struggled mightily in the second half.

We know that Gordon is a speed threat, but he cannot steal bases unless he gets on base—and he severely struggled to do that in August and September. His OBP in both August and September were lower than any other month of the season, and that was related to his walk rate (which was just 1.6 percent in the second half).

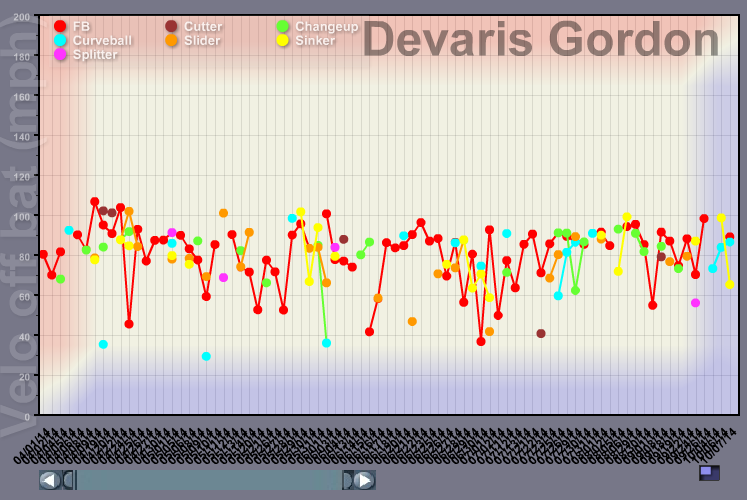

A more general indicator actually remained shockingly constant. Overall, the velocity of hits off his bat remained relatively similar throughout the season. This jives with his BABIP, which was .344 before the break and .348 after.

Thus, Gordon’s general contact profile was unchanged. He did not hit the ball softer, and that did not result in him getting on base fewer times. Instead, it is not the batting average we must look at. It is his ability to walk.

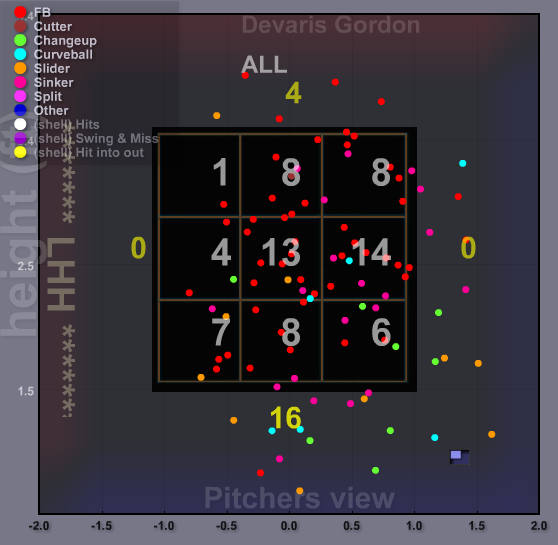

It is difficult to examine a sample size that is both large enough to draw a conclusion from and small enough to adequately visually display the overall trend. To that end, I selected two two-week periods, one from when Gordon was playing well (April 1-15 [left]) and one when Gordon was struggling (August 1-15 [right]). Each picture represents all the pitches Gordon swung at during that time.

A clear pattern emerges. In April, Gordon was able to lay off pitches outside the zone. He swung at pitches inside it, but he did not swing at many pitches that weren’t hittable. In August, though, he chased a lot more pitches, particularly ones below the zone.

Of course, with all else being equal, either sample could possibly be legitimate. There’s no particular reason that the second half should be more instructive than the first, especially given Gordon’s history as a top prospect. Except, of course, for his major league career.

Per FanGraphs’ plate discipline statistics, Gordon swung at an above-average percentage of pitches out of the zone each of his first three years in the league as well. And while those numbers steadily improved over the course of his career, they still paint a disturbing picture. It appears that Gordon’s second half was more indicative of his true talent level than was his first half.

NOTE: All statistics accurate as of 12/10/14

By Seth Victor

AriBall.com